Xact Data Discovery is now part of the Consilio family. Welcome!

Xact Data Discovery is now part of the Consilio family to build upon our global client experience delivering award-winning eDiscovery, Document Review, Talent, and Advisory solutions to corporations and law firms of all sizes. Read about the news or explore what we have to offer.

Significant Benefits to XDD Clients

- Access to Consilio’s Complete suite of solutions: Over several successful integrations and subsequent investment in its expertise, workflows and technology, Consilio has developed and grown our impressive Complete suite of solutions.

- Data Forensics & Expert Services, an experienced global team offers virtual assisted, onsite, or in-lab forensic services – over 6,000 of which are conducted annually across the world.

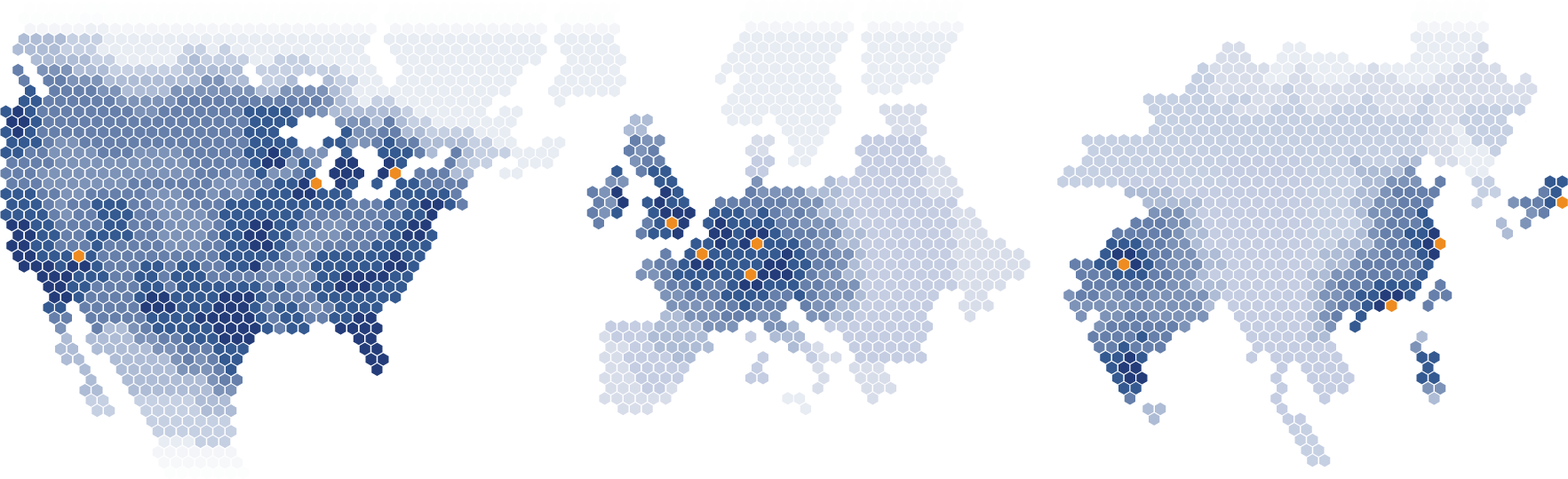

- Expanded ability to serve your cross-border matters: Consilio has geographic presence includes United Kingdom, Germany, People’s Republic of China (including Hong Kong), Japan, and India. This global reach allows for bespoke solutions to address XDD client’s cross-border and in-region challenges – with special emphasis on conforming to data hosting, data privacy / security and state secrets requirements. Consilio also has recently expanded operations in Switzerland, Canada, France and Belgium. Consilio is battle-tested by serving the most complex matters in those regions.

- More scale across more geographies = an even better service experience: Consilio Data Operations and Project Management work on a 24 x 7 x 365 follow-the-sun operational model. This means that your data processing and document productions can happen around-the-clock, regardless of your location.

- More technology options & more innovative solutions: Like XDD, Consilio has made significant technology investments – but in different, and complementary areas.

- In addition to improving upon our Relativity offering, Consilio supports its own top-rated eDiscovery platform, Sightline, recently recognized as #1 in Quality of Support amongst all eDiscovery platforms by G2 and Sightline Legal Hold, a rising compliment to your legal workflow.

- Complete Media, a top-of-market capability for video and audio reviews incorporates a class-leading phonetic indexing solution and intuitive user interface built directly in Sightline.

- Opportunities for efficiency, reduced risks & costs with Complete Enterprise: Offering clients a holistic, stakeholder-centric approach working side-by-side with lawyers, corporate IT teams, consultants and technologists, Complete Enterprise delivers a proven end-to-end suite of enterprise legal services. Each solution set we deliver, from Advisory & Transformation and Law Department Operations to Compliance and Enterprise Talent is tightly-integrated to drive efficient outcomes, reduce client risk & control cost for legal operations ― all designed to deliver as one complete enterprise experience.

Proven Expertise

End-to-End Coverage. Deep Expertise. Proven at Scale.

Consilio Complete is a suite of powerful legal services & technologies proven to deliver efficiency, quality, and cost savings for challenges of any size & type. All supported by our global experts, robust workflows, and secure, scalable technology infrastructure. Learn more about the suite or explore any of the 8 robust capabilities forming the Complete experience:

Values that Deliver

Strength through Diversity & Inclusion